NoOneImportant wrote:

> John, while I don't presume to speak of gerald, I perceive his

> comments to pertain to Continental North America, after 1620, the

> founding of the Plymouth Bay Colony. What we see develop over the

> next 140 years was something truly unique in human accounts; that

> something was formalized in the American Declaration of

> Independence, and the US Constitution. The socialist experiment,

> as noted in gerald's comments, was the initial process for the

> growing of food in the Plymouth colony - to their detriment, and

> almost extinction. Only after the futility of their socialist

> "experiment" brought them face to face with starvation did the

> colonists adopt individually tended plots - changing eventually to

> individually owned plots. Only after that change did William

> Bradford note in his history of the Plymouth Colony that the

> company never again wanted for food.

From my book:

The Colonists versus the Indians -- 1675-78

The most devastating war in American history was the Civil War, but

the most devastating war in New England's history occurred about 100

years before independence between the colonists and the local Indian

tribes. This war cast a shadow that lasted until the American

Revolution, and had an enormous influence on events leading all the

way up to the Revolution.

The standard America-centric view of this war is as follows: The

colonists and the Indians got along pretty well until the colonists

started taking too much valuable farming and hunting land. There was

a devastating war in the years 1675-76, just one of many wars that

the colonists, and later the "white man," used to steal land from the

Indians.

That's an interesting political point of view, and it's true in a

sense, but it doesn't provide any real understanding unless we expand

the scope of our vision a little bit.

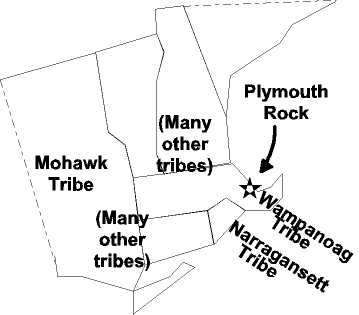

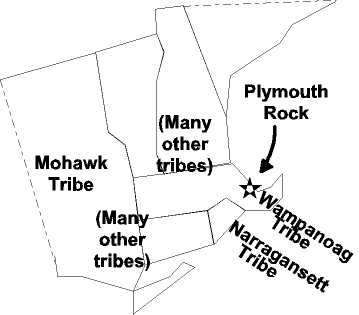

- New England in 1675. The Pilgrims had landed in 1620 at

Plymouth Rock, in the midst of the Wampanoag tribe.

In the year 1600, throughout what is now the United States, there were

some 2 million Indians within 600 tribes speaking 500 languages. What

happened, starting at that time, was a "clash of civilizations"

between European culture of the colonists and the indigenous culture

of the Indians. These cultures were so different that haven't yet

merged even today, inasmuch as many Indian tribes still live

separately on reservations. It's ironic that the American "melting

pot" has merged so many cultures, but has not yet entirely merged the

preexisting Native American cultures.

Most history books treat "the Indians" as a monolithic group, as if

they spoke with a common voice and common intent, but that's far from

the truth. There were undoubtedly many brutal wars among the 600

tribes of the time. What would have happened if no colonists and no

other outsiders had come and intervened in the life of the Indians?

What would have happened? There's no way to know, of course, but

it's likely that one or two of the tribes would have become dominant,

wiping out all the other tribes in numerous wars. That's the nature

of human societies: As they grow larger and run into each other, they

go to war, and the dominant societies survive.

For the purposes of our story, we're going to focus on just three of

those Indian tribes: The Wampanoag tribe that occupied what is now

southeastern Massachusetts (where Plymouth Rock is) and the

Narragansett tribe that occupied what is now Rhode Island, and the

Mohawk tribe (part of the Iroquois) of upstate New York.

There is some historical evidence that a major war among these tribes

had occurred in the years preceding the colonists' arrival at Plymouth

Rock, probably in the 1590s. The Wampanoag and the Narragansett tribes

were particularly devastated and weakened by that conflict.

So, when the pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock in 1620, in the midst

of the Wampanoag tribe, they had little trouble developing a pleasant

cooperative relationship. The Wampanoag Indians were in an awakening

period, and they taught the colonists how to hunt and fish, and in

autumn of 1621, they all shared a Thanksgiving meal of turkey and

venison.

Most significant was the colonists' early "declaration of

independence." Before the colonists landed in 1620, they signed the

Mayflower Compact, where they agreed that they would be governed by

the will of the majority. This laid the framework for the view that

neither the king nor parliament had any say in colonial government.

And why would they need the King anyway? After all, they could

provide for themselves, and they were friendly with the Indians.

This friendliness extended to trade. Before long, there was a mutually

beneficial financial arrangement between the Indians and the

colonists. The colonists acted as intermediaries through whom the

Indians developed a thriving business selling furs and pelts to the

English and European markets, and they used the considerable money

they earned to purchase imported manufactured goods.

There were two particular Indian chiefs who are important to this

story: one is a father and the other is his son, who took over when

the father died in 1660.

The father's name is Massasoit, chief of the Wampanoag Indians, the

Indian tribe most familiar to the Massachusetts colonists.

We have no way of knowing Massasoit's history. He was born around

1580, and so he must have been alive during the devastating war with

the Narragansett. In fact, since he became Chief, he may well have

been a hero who fought in the war in his teen years. With his

personal memory of the devastating results of the last all-out war, he

would not want to go through another war again unless absolutely

necessary.

We have no way of knowing the details of what the Indian tribes had

fought over, but chances are it was over what most wars are fought

over -- land. Each tribe wanted the best hunting, fishing and

farmland for its own use. But Massasoit maintained friendly

relationships with the colonists because of the financial benefits,

and because he was a wise, elder leader who didn't want another big

war in his lifetime.

Several dramatic changes occurred in the 1660s, when Massasoit died.

"The relationship between English and Native American had grown

inordinately more complex over forty years," according to Schultz and

Tougias. "Many of the important personal ties forged among men like

Massasoit and Stephen Hopkins, Edward Winslow, and William Bradford

had vanished. The old guard was changing on both sides, and with it a

sense of history and mutual struggle that had helped to keep the

peace."

Massasoit was replaced as Chief by his oldest son, Wamsutta -- who

died under mysterious circumstances that were blamed on the

colonists. The younger brother, Metacomet, nicknamed King Philip by

the colonists, became Chief.

Things <i>really</i> began to turn sour in the 1660s for another

reason: Styles and fashions changed in England and in Europe.

Suddenly, furs and pelts went out of style, and the major source of

revenue for the Indians almost disappeared. This resulted in a

financial crisis for the Indians, and for the colonists as well, since

they were the intermediaries in sales to the Indians.

But that's not all. Roughly 60-70 years had passed since the end of

the last tribal war. The Mohawk War (1663-80) began, and created

pressure from the west. The colonists were establishing ever-larger

colonies in the east. In this pressure cooker atmosphere, the

Wampanoag tribe, led by a young chief anxious to prove himself,

allied with their former enemy, the Narragansett tribe, to fight

their new enemy, the colonists.

One of the most fascinating aspects of history is how two enemies can

carry on a brutal and almost genocidal war, and then, 80 years later,

can be allies against a common enemy. This appears to be the way

things are going today with our old World War II enemies, Germany and

Japan, and it's certainly true of protagonists in the most

destructive war in American history, the Union and the Confederacy in

the Civil War.

In this climate of general war tensions and financial distress, we

see the same pattern for how a major war occurs: There's a

generational change, then a period of financial crisis, then a series

of provocative acts by both sides, each of which is a shock and

surprise to the other side, and calls for retribution and

retaliation.

It's important to understand the role of all three of these elements.

In particular, without the generational change, the provocative acts

are met with compromise and containment, rather than retribution and

retaliation.

This is particularly important in understanding what's going on when

one side is provocative and the other side is compromising. This

often means that the generational change has occurred on the first

side, but not yet on the second.

In our own time, the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center was a

provocative act by Islamist extremists, but was met by no more than a

criminal trial for the perpetrators; the 9/11/01 attack was met with a

war against Afghanistan.

The actions of the colonists, in the face of provocations by the

Indians, seemed to display a similar range of goals. In the 1660s,

perpetrators were brought to trial, and executed if found guilty of

the most serious crimes.

The trial process was brought to a head in 1671, when King Philip

himself was tried for a series of Indian hostilities, and required by

the court to surrender all of his arms; he complied by surrendering

only a portion of them.

After that, the trial process seems to have fallen apart, as the

colonists began to lose their patience and willingness to compromise.

Trials were still held, but they became mere provocations: they were

kangaroo courts with the results preordained, and the Indian

defendants were always guilty.

These provocations kept escalating, until King Philip's War began

with Philip's attack on the colonists on Cape Cod.

The war was extremely savage and engulfed the Indians and the

colonists from Rhode Island to Maine. There were atrocities on both

sides, and the war ended with King Philip's head displayed on stick.

His wife and child were sold into slavery.

This was the most devastating war in American history on a percentage

basis, with 800 of the 52,000 colonists killed. (It was devastating

for the Indians as well.)

http://www.generationaldynamics.com/pg/ ... #lab100036